Markets

Markets are crucial to ensure a cost-effective competitive energy transition. This is why at Eurelectric we advocate for a fully competitive, integrated internal energy market in the EU. We are committed to lead Europe’s energy transition by decarbonising our economy with clean and renewable power.

For net-zero to become a reality, however, our electricity market must be fit for purpose.

But how does the electricity market work and how did we get to where we are today?

What are electricity markets?

Electricity markets are platforms where electricity is traded, bought, and sold among various participants across different timeframes.

Just like any other commodity markets, electricity markets follow the economic principles of demand and supply, aiming at ensuring that demand is served at any moment in time in the most cost-effective way. In very basic terms, electricity generators sell a substantial portion of their production to consumers on the wholesale market well before actual of delivery. To align demand with supply, various markets operate with different timeframes, such as day-ahead or forward contracts. These purchased volumes are then sold by suppliers to consumers, like businesses and households, through the retail market.

What’s the history of the European electricity market ?

In the early 20th century, electricity was primarily produced and distributed by state-owned companies and sold in national markets with restricted competition. It was not uncommon for a single entity to control the entire value chain from generation to power distribution. The intention was to provide a reliable electricity supply to citizens, often with limited attention to for market efficiency, investment incentives and technological innovation.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the European Commission began advocating for the liberalisation of energy markets across the Union. The idea was to introduce competition and incentivise system efficiency, as well as to create a single market for electricity that would facilitate cross-border trade and increase security of supply.

This led to a wave of privatisations and a reform of the electricity industry across Europe, as many state-owned companies were required to separate their generation, transmission, and distribution activities into different legal entities. This process was intended to prevent monopolistic behaviour and allow for more market-driven pricing.

Market liberalisation has been successful in achieving many of its intended goals. The creation of a single European energy market facilitated cross-border trade and increased security of supply, While the separation of generation, transmission, and distribution activities enabled greater competition and market efficiency.

Overall, the development of a competitive and integrated European electricity market has been a complex and continuous process, yet its evolution has led to a more dynamic, market-driven system that is better suited to the needs of modern society.

Additionally, a more market-based and integrated system required the creation of new regulatory bodies, as well as new trading platforms and market rules.

How does the European electricity market work?

Today, the European electricity market is governed by a set of rules and regulations that are designed to promote competition, ensure security of supply, and incentivise investment in renewable energy sources. These rules are enforced by national regulatory agencies in each Member State and overseen by the European Union’s Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) at European level.

What is ACER’s role?

Established in 2009, the ACER was founded to promote the cooperation of national energy regulators across the EU member states to create a more integrated and competitive internal energy market.

As the new regulatory framework for energy markets enabled increased cross-border cooperation, the absence of regional and cross-border oversight could have posed potential challenges. This lack of oversight might have resulted in divergent decisions by national regulators and lead to unnecessary delays. Recognising this risk, the ACER was established to address these issues and ensure consistent and coordinated regulatory approaches.

What is the difference between the electricity wholesale and retail markets?

At the heart of the electricity market is the wholesale market, where electricity is bought and sold between generators, traders, suppliers, and aggregators. Prices in this market is determined by supply and demand, fluctuating based on production and consumption. Thus ensuring that demand is met efficiently at any given time .

On the other hand, the retail market involves the sale of electricity by suppliers to end-users, including include businesses and households.

How are wholesale prices formed?

Wholesale prices are formed as a result of the competition between generators striving to sell their production and meet the demand forecasted by transmission operators (TSOs) across different timeframes (e.g. in day-ahead, intraday, and forward markets) at the lowest possible cost.

Thus, the wholesale market operates by clearing demand at the most affordable cost possible.

The generators are dispatched in an order starting from the least expensive to the most expensive energy source until the energy supply meets the demand. The generators submit their bids, and the final price is set at the rate proposed by the last power plant that was activated to fulfil demand, known as the marginal plant.

As a result, the final price equals the variable marginal cost of the last power plant that was required. All the generators that supplied energy during that period will be paid the same rate as the last activated producer. This payment is referred to as inframarginal rent, and it ensures that the fixed investment costs are covered.

The advantage of this system is that it encourages investment in solar and wind power, which have very low marginal costs, and incentivises an efficient use of different generating assets in relation to their carbon emissions.

How are retail prices formed?

The retail bill refers to the cost that a customer has to pay for every kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity consumed during a specific timeframe.

The largest component of retail prices is usually the cost of the electricity itself which is influenced by the wholesale market price but is ultimately agreed between the customer and supplier. Consumers can adhere to either a fixed or variable price depending on their energy needs and degree of flexibility.

In addition to the wholesale price of electricity, retail electricity prices can also include a range of other charges and fees that are designed to cover the costs of transporting and distributing electricity to consumers. These charges may include fees for transmission and distribution, as well as fees to cover the costs of metering and billing.

Retail electricity prices also feature various taxes and levies, which can vary between countries. These taxes and levies can be used to fund renewable energy programs, support energy efficiency measures, or cover other government expenses.

While customers cannot do much about their bill’s network fees, taxes, and levies, they can always compare the offers and services provided by their suppliers with their competitors. Thanks to market liberalisation, customers are thus free to switch providers and opt for the utility with the best solution for their needs.

What are the frameworks that govern the EU electricity markets?

Between 1996 and 2009, three packages containing Electricity Directives and Regulations established a set of common rules for internal energy market. EU Member States intended to put an end to the traditional monopolies by organising competitive power exchanges, both within the countries and across their borders. This would offer customers, be they citizens or businesses, competitive prices; give efficient investment signals and higher standards of service; help maintain security of supply and contribute to sustainability goals.

In 2019, the Clean Energy Package brought new changes to reflect the higher decarbonisation ambitions. For instance, it deciding the phase-out of subsidies to generation capacity emitting 550gr CO2/ kWh or more. Moreover, it put consumers at the centre of the clean energy transition, enabling their active participation in the electric ecosystem.

In light of the energy crisis that hit Europe mid-2021, further escalated by Russia’s induced gas crunch, several EU Member States have questioned the functioning of the market, proceeding with ad-hoc interventions to limit the impact of higher prices on consumers. Regulators have assessed the situation and confirmed the proper functioning of the internal market.

In 2022 the European Commission launched a process to reassess the design of electricity markets and came with a new legislative proposal in 2023. This reform was originally called for by European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen in her 2022 State of the Union Speech to address Russia’s induced gas crunch and consequent energy price crisis. The reform also aimed at attracting more investments into clean and renewable power generation.

Since then Member States made headlines with their own reform proposals. From the radical Spanish and French non-papers to the more conservative joint letter from Germany and six other Member States, the debate reached the highest levels of EU policymaking. At stake was Europe’s path to net zero and energy security.

The electricity industry warned against revolutionary approaches to the current market design and called for an evolution rather than a revolution of the market:

“The liberalisation of the power sector has served Europe well and is today a guarantor of security of supply and solidarity. Looking ahead, we should continue to develop and complete the market rules to ensure that they are fit for purpose in the future as well.” – said Eurelectric’s President and E.ON’s CEO Leonhard Birnbaum.

The European Commission ultimately proposed a well-balance reform aimed at shielding consumers from short-term price volatility without destroying the short-term price signals necessary to direct investments. To achieve this, the reform envisaged a greater role for long-term hedging instruments and contracts such as power purchasing agreements (PPAs) and two-way contract for difference (CfDs). The aim was to mitigate mitigating the impact of short-term markets on the price of electricity paid by consumers without destroying the short-term price signals necessary to direct investments.

Long-term contracts such as a market-based Power purchasing agreements (PPA) or a state-mediated contracts for difference (CfD) allow market participants to negotiate a fixed price for part of their energy demand thus avoiding excessive exposure to short-term market prices. These contracts provide clear long-term price signals that reassure investors. By offering long-term visibility on returns and stable revenue, such contracts help investors and encourage them to reinvest in renewable generation or additional storage and flexible capacity.

As we have detailed what a PPA is in a previous article, we will now turn to two-way contracts for difference (CfDs).

What are power purchasing agreements (PPAs)?

As detailed in our article, power purchase agreements, often referred to in short form as PPAs, are long-term contracts between a supplier and buyer of electricity. The energy provider is generally an electricity generator, and the buyer is often a utility. More and more, however, electro-intensive industries and other corporates have been signing up to the agreements too.

A PPA includes all the terms of the agreement, such as the amount of electricity to be supplied, the negotiated price, who bears what risks, the required accounting, and the penalties if the contract is not honoured. As it is a bilateral agreement, a PPA can be adapted to the wishes of the parties involved, so the supply contract can take many forms.

This is a transformative instrument for the energy transition. Through such contracts, renewable project developers have access to finance to deploy new renewable energy sources, while the other party gains access to stable renewable electricity supply at a predictable price. How does a PPA accomplish this?

Simply put, the buyer and the energy provider or generator come together to negotiate a price at which the provider will sell electricity to the energy user, and the volume of electricity to purchase from the generator at that price point. This is in place of leaving the sale and sourcing of power to the spot market where prices are subject to volatility – especially over the past year.

What are contracts for difference (CfDs)?

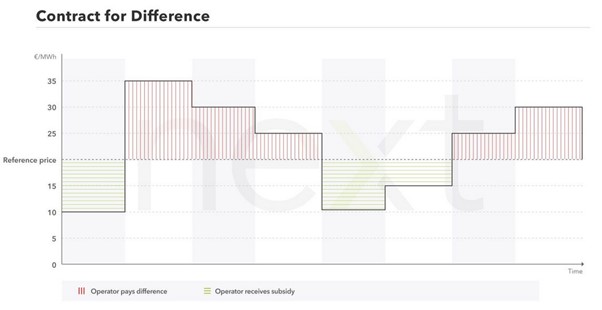

Two-way contracts for difference (CfDs) is an agreement wherein the buyer, usually a public counterparty, pays the agreed-upon ‘strike’ price to the seller, often a renewable or low-carbon plant operator, for the contracted volume. In return, the seller pays the reference index to the buyer.

Contracts for difference are mechanisms to foster investments in a power generation asset with significant upfront costs and capital-intensive expenses (CAPEX) by providing price visibility over the long term.

Originating from financial practices, CfDs function as financial derivative contracts, where the actual good is not physically traded as the transactions are purely financial.

Within CfD contracts, two parties enter into an agreement to exchange payments based on a ‘strike price’. Whenever there is a fluctuation between the reference index price and the strike price agreed in the contract payments are exchanged between the contracting parties, without the actual good ever-changing hands.

In the case of a support mechanism, the buyer does not necessarily get access to the associated energy volume, but only pays or receives symmetrically to or from the seller the difference between the strike and reference prices.

In a traditional two-way CfD, when the strike price exceeds the market price, the deficit - revenues below the strike price - are collected by the generator. On the other hand, when the strike price is below market price, the surplus - revenues above the strike price - is retroceded to the buyer to reach the strike price.

Find out more about CfDs in our CfD explainer.

Why is market integration important?

Establishing an integrated energy market in the EU is the most economical method to guarantee that citizens have access to reliable and reasonably priced energy. By implementing common energy market regulations and building cross-border infrastructure, energy generated in one EU country can be distributed to consumers in another country. This approach maintains competitive prices by spurring competition and providing consumers with the option to choose their energy suppliers.

By permitting the free flow of electricity to areas where it is most in demand, society will increasingly benefit from cross-border trade and competition. This would in turn translate into:

o Greater efficiency and more competition between suppliers as obstacles are steadily broken down between closed national systems, creating the space for the emergence of innovative companies and services.

o Incentivised investment in capital-intensive clean technologies, both in terms of the generation and the distribution of electricity. Securing these investments is essential to Europe meeting its decarbonisation ambitions as it provides the flexibility and firm capacity needed to complement variable renewable energies and facilitate their integration into the distribution grid.

How has the 2022 energy crisis impacted markets?

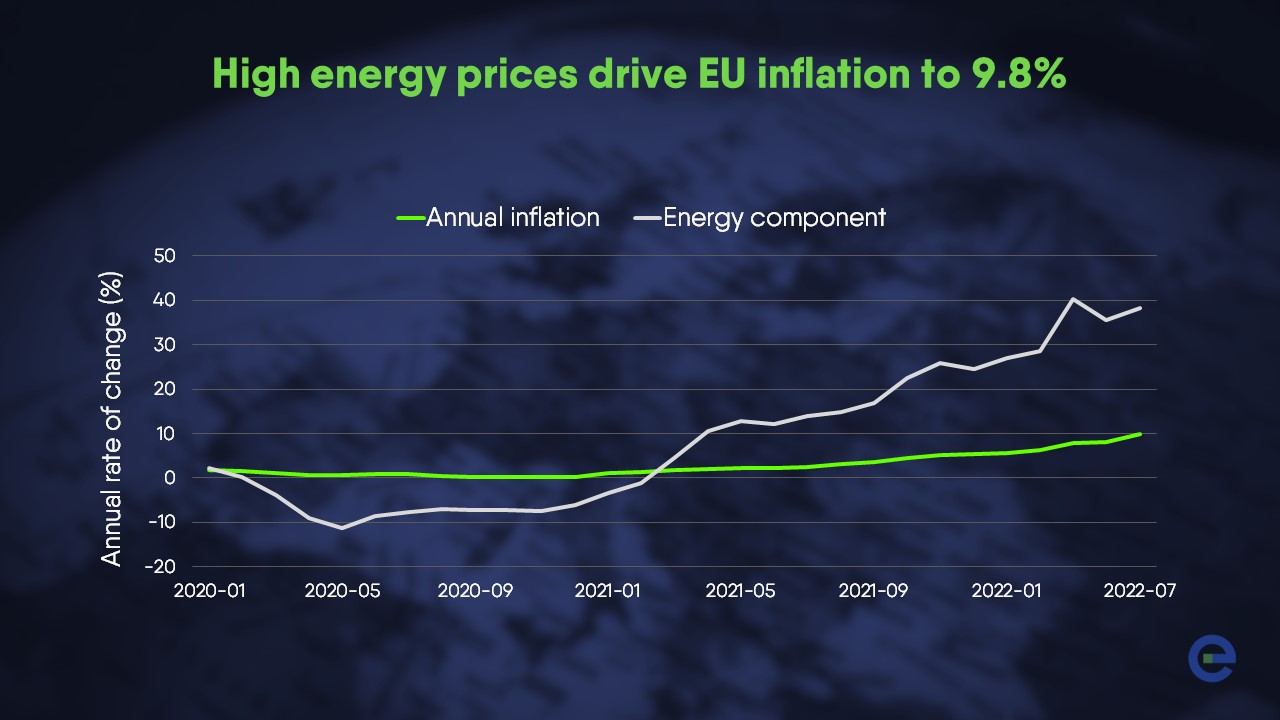

Inflation began to rise as the continent emerged from the Covid crisis and economic growth rebounded, coupled with a steady increase in energy prices starting from July 2021. This situation was compounded by Russia's military aggression in Ukraine and its tighter control over oil and gas supplies. Natural gas prices soared, leading to a decline in industrial output, an increase in household bills, and further driving up inflation – shows our Power Barometer.

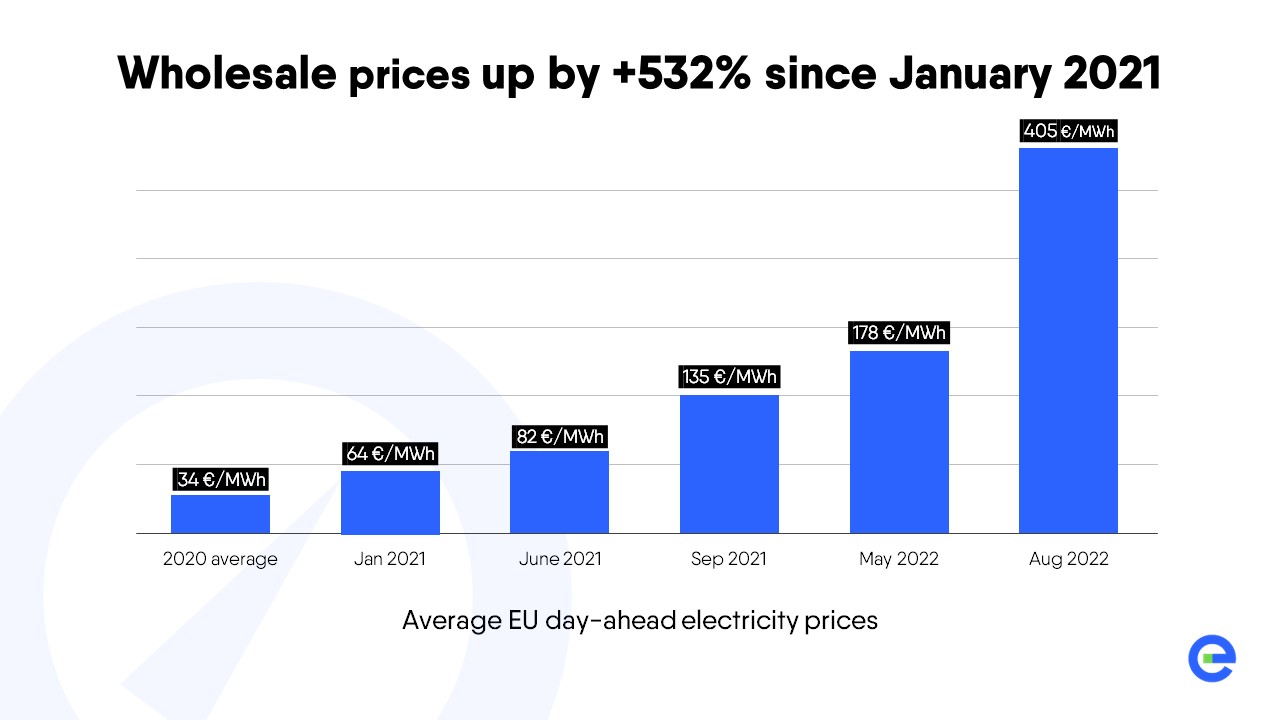

As the global demand for fossil fuels surged, electricity prices began to rise noticeably from June to September 2021. This trend persisted throughout 2022, with average EU day-ahead prices peaking at €405/MWh in August 2022, a staggering 532% increase from January 2021. By late 2022, these changes had begun to impact retail prices.

The energy crisis was precipitated by Russia's deliberate actions to disrupt Europe's energy supply. As a result of the limited flow of gas into Europe, we experiencied a supply crisis that had immediate effects on the European electricity markets. Shortages in nuclear and hydropower generation, exacerbated the situation. The latter are now back to normal.

It is crucial to recognise that the high electricity prices were not caused by the market design. On the contrary, the internal market delivered significant benefits. Rather, the energy price surge was the result of a gas crisis that had a significant knock-on effect on electricity prices, despite the fact that most of the measures and interventions adopted in the EU were focused on the electricity market.

Since then electricity prices have gradually lowered although they remain higher than pre-pandemic levels.

But how are electricity prices made? Well, have you ever heard of the wholesale merit order?

What is the wholesale merit order?

The merit order is the ranking of power plants according to their respective generation costs. It is established based on the variable costs of each power plant, calculated in €/ kwh. Renewables have the lowest variable costs, as sun and wind are for free. The merit order therefore ranks renewables first, followed by nuclear, gas, coal, and oil fuel.

The more solar and wind generation comes online, the lower the wholesale power prices will be. They can even lead to negative power prices, whose occurrence has grown from zero in 2010, to 375 hours in 2018 and 1827 in 2020.

Looking at other technologies, we know that nuclear power generation has lower operational costs than fuel-based plants, uranium being less expensive in €/ kwh than gas, coal and oil. Fossil fuels are not only exposed to commodity pricing, and external volatility, but they are also subject to CO2 pricing – having to pay for each ton of carbon emissions.

For instance, 100 kwh of coal-based electricity produces on average one ton of CO2, while 100 kwh of gas-fired electricity emits 0,2-0,3 tons of carbon. This cost is part of the variables considered when generators make their bid in the wholesale. The carbon price in the EU Emissions Trading System has increased in recent years, in response to Europe’s increased decarbonisation ambitions.

With the exception of some European countries, such as Cyprus or Estonia, that still rely on oil capacities to cover 95% and 58% their electricity demand, these oil fuelled assets are most often used as peaking plants, to serve peak demand for a limited number of hours over the year.

As the energy crisis unfolded, gas became the price setter for electricity, thus driving power prices up. Oil-based generation assets played a more prominent role to save on natural gas, but given their high operational costs, low efficiency and environmental constraints, this thermal capacity will not make a comeback into the baseload mix.

Reaching the optimal electricity market design reform

For months Eurelectric advocated for a well-balanced market design reform in order to ensure the much needed investments into Europe’s decarbonisation.

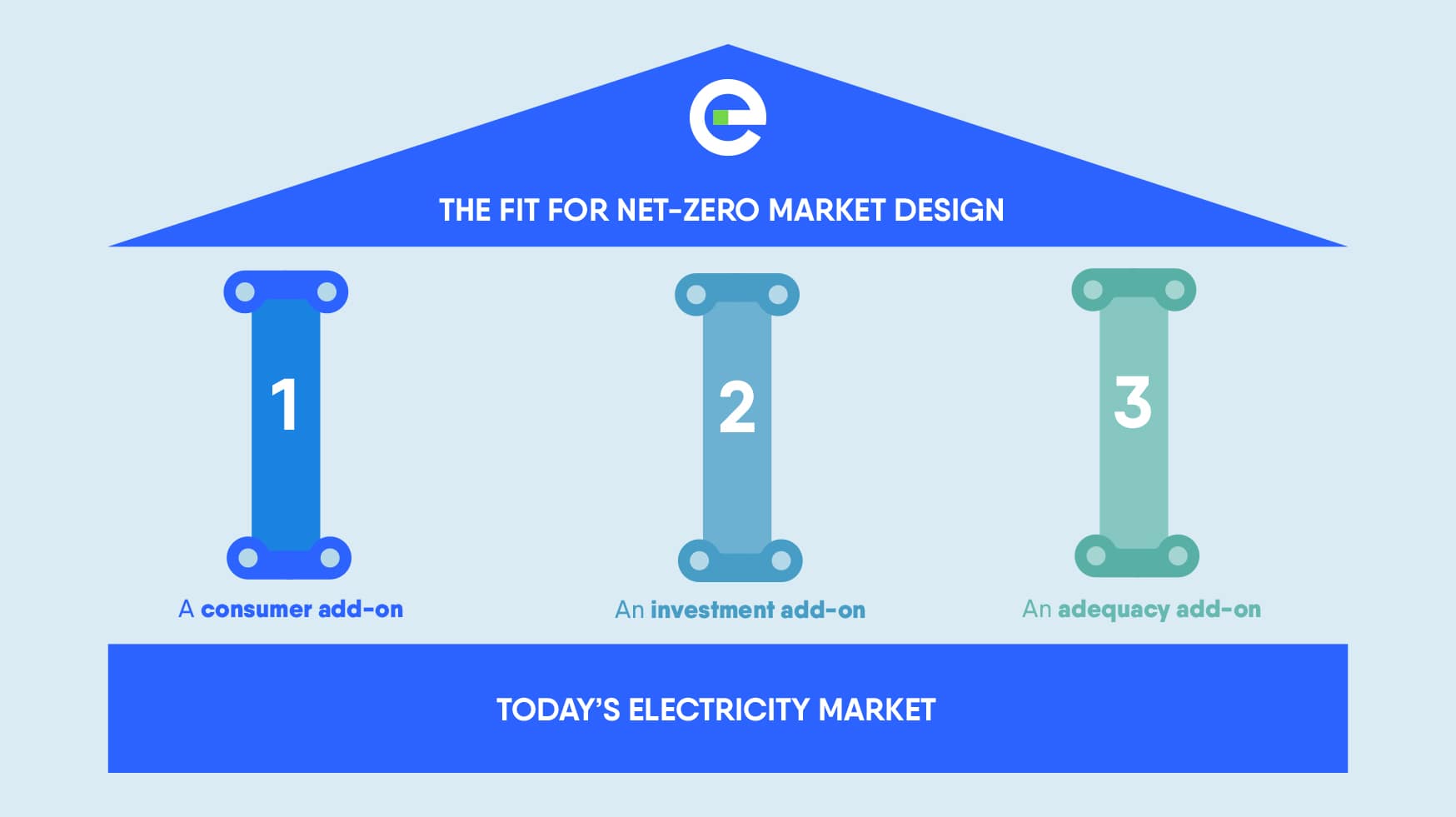

We suggested adding three new pillars to the current market design:

- first,a consumer contracting and engagement framework to more consistently transfer the benefits of cheaper clean and renewable energy to consumers;

- second, a market-compatible investment framework to ensure the right investment signals for capital-intensive renewable and low-carbon technologies; and

- third, a security of supply framework to meet the evolving power system requirement

In April 2024 the reform was formally adopted by the European Parliament. Eurelectric’s Secretary General Kristian Ruby welcome the agreement and added:

“In the coming decades, our industry will need to invest heavily and we have now the market design in place. We need regulatory stability so let's work with this system.

Looking to the next mandate, the EU need to be laser focused on implementation, infrastructure and investment. In light of the scale of the needed investments and the difficult economic environment, we may need to develop additional de-risking tools.”

Beyond market design, the need for the electricity sector to secure massive investments remains, given the leading role our sector is taking in Europe’s decarbonisation. Some €100 billion per year are needed in clean generation and storage, in addition to €38bn per year in distribution grids, between today and 2030. The electricity sector is ready to play a leading role in these investments provided a consistent combination of market design, regulatory framework and energy policies are in place to deliver the needed investments to reach carbon-neutrality by 2050. This includes a stable financial framework that underpins utilities’ investments in the green transition.

Zooming into market integrity measures and sustainable finance

Utilities are active on both physical and financial markets on a continuous basis. Indeed, utilities buy and sell electricity on wholesale markets to ensure that they can meet their contractual obligations at any time. This is necessary because electricity cannot be stored, and the amount of electricity produced at a certain time is subject to swings. Utilities tend to sell their power production well before delivery on forward markets, thereby “hedging” their production risk and covering the procurement risk of retail suppliers. Swings in the amount of electricity actually produced on the day of delivery are then evened out on short-term markets.

To ensure fair competition on the different marketplaces used by electricity utilities, the power sector is subject to a sector-specific regime ensuring fair competition on wholesale energy markets. The REMIT Regulation, which ensures the transparency and integrity of electricity markets, was recently revised to adapt its framework to recent market developments. Eurelectric consistently argued for maintaining a regime adapted to the specificities of the electricity market. Indeed, it is important that the concepts introduced in REMIT II do not inflate legal uncertainty due to their misalignment with the functioning of electricity markets.

In the medium term, it is important that electricity markets are not treated like any other financial market through legislation such as MiFID or EMIR. This is true both concerning the products traded and the actors trading on those markets. As mentioned before, utilities mostly trade on physical and financial markets to hedge different risks associated with their production. If they were subject to the same rules as banks, this would eventually restrict their ability to finance the energy transition and increase the cost of electricity.

Finally, utilities also need a sustainable finance framework that allows them to raise sufficient funds for investments into low-carbon projects on capital markets. Electricity companies are already making use of the EU Taxonomy on sustainable economic activities, which provides a clear view of investments with a positive environmental footprint. In addition, the revised CSRD aims to put information about utilities’ sustainability impacts on par with reporting on their financial results. As the power sector puts everything in place to comply with these rules, it is important that regulators do not lose sight of the final objective of the sustainable finance framework: channelling sufficient funds towards sustainable investments.

We need you

Ambitious targets to implement, new challenges to face and the climate clock keeps on ticking faster targets: the energy industry needs all hands on deck to succeed!

Boosting the number of green workers in Europe is now crucial to implementing our decarbonisation targets. Europe must equip its workforce with the right skills to deliver the efficient, clean, and safe electrical installations we need. In this way electrification can also help to fuel local growth and career opportunities – shows the Electrification Alliance Manifesto.

This means expanding the ‘pipeline’ of workers by reaching out to young people, existing professionals and workers looking to change careers. We can do this by making green jobs more attractive, increasing gender diversity, ensuring that technical education and apprenticeships are properly valued, and making upskilling readily available. Europe must make the most of the Skills chapter in the Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA).

Contact us to know more about electricity markets, learn about our upcoming products and keep the current with our events!