A CfDs explainer

The EU is close to adopting of the much debated reform of the Electricity market design (EMD) . This reform was originally called for by European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen in her 2022 State of the Union Speech to address Russia’s induced gas crunch and consequent energy price crisis. The reform also aimed at attracting more investments into clean and renewable power generation.

Since then Member States made headlines with their own reform proposals. From the radical Spanish and French non-papers to the more conservative joint letter from Germany and six other Member States, the debate reached the highest levels of EU policymaking. At stake was Europe’s path to net zero and energy security.

The electricity industry warned against revolutionary approaches to the current market design and called for an evolution rather than a revolution of the market:

“The liberalisation of the power sector has served Europe well and is today a guarantor of security of supply and solidarity. Looking ahead, we should continue to develop and complete the market rules to ensure that they are fit for purpose in the future as well.” – said Eurelectric’s President and E.ON’s CEO Leonhard Birnbaum.

The Commission ultimately managed to propose a well-balance reform aimed at shielding consumers from short-term price volatility without destroying the short-term price signals necessary to direct investments. To achieve this, the reform envisaged a greater role for long-term hedging instruments and contracts such as power purchasing agreements (PPAs) and contract for difference (CfDs).

As we have detailed what a PPA is in a previous article, we will now turn to contracts for difference (CfDs).

What are contracts for difference (CfDs)?

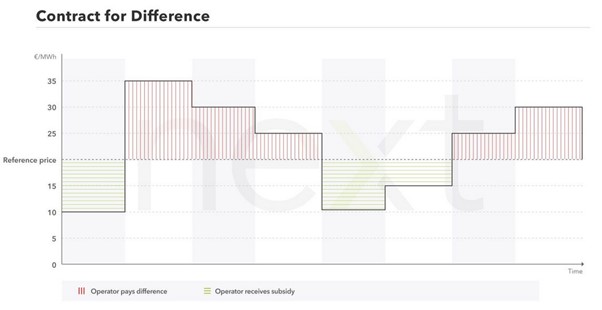

Two-way contracts for difference (CfDs) is an agreement wherein the buyer, usually a public counterparty, pays the agreed-upon ‘strike’ price to the seller, often a renewable or low-carbon plant operator, for the contracted volume. In return, the seller pays the reference index to the buyer.

Contracts for difference are mechanisms to foster investments in a power generation asset with significant upfront costs and capital intensive expenses (CAPEX) by providing price visibility over the long term.

What is the strike price?

In the power sector, the strike price refers to the predetermined price at which the plant operator will receive payment for the electricity it produces. The strike price serves as a key component in providing stability and financial certainty for renewable and low-carbon energy projects, incentivising investment in clean energy infrastructure.

Setting the strike price competitively through an auction process is a common practice to ensure that the strike price reflects the current market conditions and fosters cost-efficiency in projects.

What is the reference index price?

A reference index price is the benchmark price against which the actual market price of electricity is compared to determine payment obligations between the parties involved in the contract. This ensures fairness and transparency for determining payment obligations based on actual market conditions.

The reference price is typically the price on the day-ahead market and can be weighted averaged across a given period, such as a month, using a standard profile. The contracted volume may be the actual production of the plant, or a standard production profile.

How does a CfD work?

Originating from financial practices, CfDs function as financial derivative contracts, where the actual good is not physically traded as the transactions are purely financial.

Within CfD contracts, two parties enter into an agreement to exchange payments based on a ‘strike price’. Whenever there is a fluctuation between the reference index price and the strike price agreed in the contract payments are exchanged between the contracting parties, without the actual good ever-changing hands.

In the case of a support mechanism, the buyer does not necessarily get access to the associated energy volume, but only pays or receives symmetrically to or from the seller the difference between the strike and reference prices.

In a traditional two-way CfD, when the strike price exceeds the market price, the deficit - revenues below the strike price - are collected by the generator. On the other hand, when the strike price is below market price, the surplus - revenues above the strike price - is retroceded to the buyer to reach the strike price.

Let's now hear it from our experts about the functioning of these hedging instruments!

Why are CfDs relevant for the EU?

The EU 2023 electricity market design reform puts forward two-sided CfDs as the single support mechanism for direct price support to new capacity but leaves a range of design issues open.

As Member States have different energy mixes, there cannot be a one-size-fits-all contract. This raises questions on how to optimally design this support mechanisms.

“Two-way CfDs are a win-win for both producers and consumers. They can be a very powerful hedging tool but also a risk if not properly designed. Our guidelines aim to make sure these long-term instruments remain market-based, voluntary and balanced in a way that does not drain liquidity from forward markets nor distort the efficiency of short-term markets” – says Eurelectric’s Policy Director Cillian O’Donoghue.

Five Issues with current traditional CfDs

Eurelectric together with Compass Lexecon has just came out with a study to address five key issues in the current design of traditional to-way CfDs. Let’s explore them one by one.

1. Traditional two-way CfDs can distort dispatch incentives, as plants no longer face incentives to increase production in high-price hours

One of the key drawbacks of traditional two-way CfDs is that plant operators are not encouraged to optimise the production of their plants according to market signals Because revenues across all hours of production equal the strike price, there is no incentive to ramp up production during periods of high prices, schedule maintenance during low-demand periods, curtail output during times of low or negative prices, or invest in power plants designed to capture above-average market prices with flexible generation profiles.

The issue of dispatch distortion becomes particularly problematic during periods of negative prices, when energy production is incentivised even when there is excess supply in the system. Consequently, regulations like the revised Guidelines on State aid for climate, environmental protection and energy (CEEAG) have suspended renewable support during negative price events, with exemptions available for small-scale installations.

2. Referencing the CfD on the day-ahead market can draw liquidity away from other markets

Plant operators risk significant losses when trading on markets other than the reference market if prices fall below expectations or if the traded volumes exceed actual production. To minimise this risk and secure the strike price, operators often concentrate their trading and hedging activities on the reference market, typically the day-ahead market.

However, this concentration of trading activity in the day-ahead market may divert liquidity away from other forward markets, potentially erecting barriers to trading and undermining overall market competition. Moreover this issue could be further exacerbated as the proliferation of renewable and low-carbon generation assets under CfDs progresses.

Therefore, enhancing forward market liquidity is crucial to safeguard consumers and industries by providing robust forward hedging opportunities.

3. An efficient risk allocation across developers and consumers needs to address trade offs

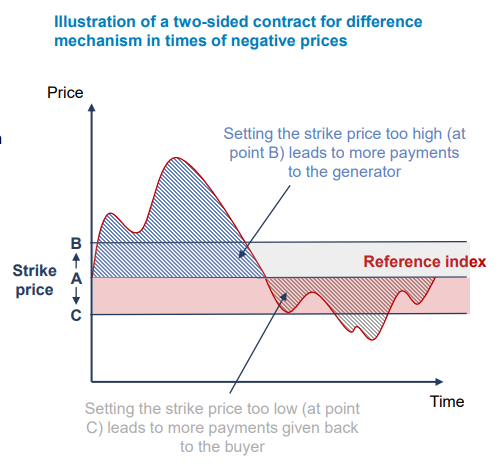

Setting the strike price entails some trade-offs in allocating costs and risks between parties.

When the strike price exceeds cost coverage, producers rely more heavily on CfD payments, increasing costs for consumers. Conversely, setting the strike price below optimal levels risks insufficient revenues to attract renewables, low-carbon, and flexible assets crucial for meeting our decarbonisation objectives.

The method of setting the strike price—whether through competitive or administrative processes—impacts risk allocation. Beyond the strike price, other CfD design elements, such as the choice of reference price, contract duration, termination clauses, and regulatory uncertainties, also influence risk distribution between parties.

4. The method to allocate the costs and benefits of CfDs can distort end-consumer price signals

The allocation of costs and benefits of CfDs presents various challenges. A clear example is deciding whether to distribute costs via taxes or electricity bills and how to fairly redistribute revenues among consumers and industries.

Regardless of the method, it’s crucial to make sure the redistribution of such costs and benefits is carried out in a timely manner for protecting consumers and industries while preventing distortion of price signals. Failure to distribute them promptly may disrupt price signals and weaken hedging strategies.

5 Avoid a ‘crowding out’ effect

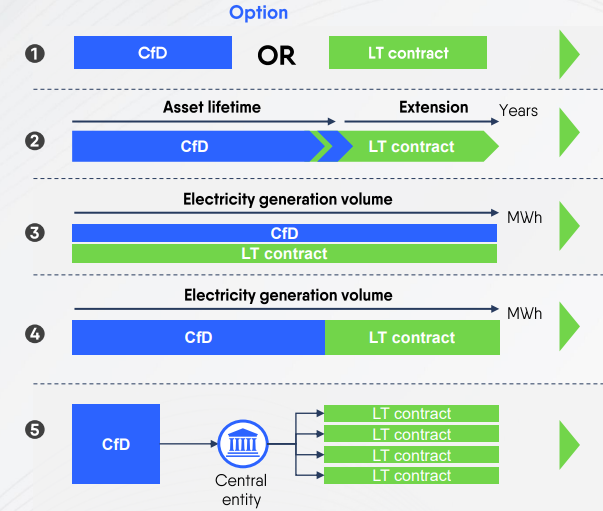

While contracts for difference may be alternatives to other long-term contracting and hedging options, they should not replace other tools like PPAs or bespoke market-based arrangements. Developers should have the flexibility to choose which volumes are covered by CfDs through voluntary, competitive, and market-based participation.

Over time, long-term contracts can complement CfDs, securing revenues at the end of the initial CfD lifetime or hedging repowering projects. Additionally, developers and plant operators may opt to hedge price exposure within the CfD design with long-term contracts for the same volume.

Additionally, CfDs can be subdivided into shorter-term contracts by the counterparty, potentially serving as a source of long-term contract supply rather than just a complement or substitute. For this subdivision to occur, Guarantees of Origin should be allocated to the counterparty.

Moreover, if a CfD only covers a portion of the generation volume (i.e. 'carve-out'), other long-term contracts can complement the remaining production volumes. To issue 'green' long-term contracts, Guarantees of Origin should be allocated to plant operators.

What are Guarantees of Origin?

A guarantee or origin (GO) is an electronic document that proves to the final customer that a quantified amount of electricity originates from a specific energy source, e.g., renewable or cogeneration. By ensuring the traceability of renewable electricity, GOs promote the production and consumption of green electricity and promote investments into renewables. A supplier who buys GOs shows his/her appreciation of the corresponding technology and provides additional revenues for the original generator. This incentivises market participants to further invest in those technologies that yield the highest prices for GOs.

Nailing the optimal CfD - How can the design of contract for difference be improved?

An efficient CfD design should carefully balance various objectives to facilitate investments at the lowest cost for consumers, while also ensuring that market participation remains conducive to the stability and efficiency of the system.

In particular CfDs should:

- Support the build-up of renewables and low-carbon assets to meet renewable and decarbonisation targets as well as security of supply requirements by providing a stable revenue stream over a long period to the developer;

- Achieve political objective at a minimal total cost, considering all costs net of value provided – it could help ensure consumer protection through cost minimisation and effective balance in risks and rewards in the contract design;

- Ensure that market participants retain sufficient incentives for optimal and system-friendly participation in wholesale markets (short term and long term) based on price signals;

- Promote efficient power plants design and location to meet the power system’s needs by producing high value electricity such as location or design choice allowing to produce in evening-peak, winter, etc rather than just maximising overall production;

- Bring the benefits of renewables and low-carbon generation assets more directly to end consumers, by contributing to consumer hedging.